David Hammons, one of the greatest living artists, has two important lessons for entrepreneurs:

(1) The truth is oblique, never transparent. To find the truth, you have to sift through the clues it left behind, not question it head-on. And (2) you have to seek those clues everywhere. In the whole neighborhood, in the whole world– not just on your block.

David Hammons is a legend. The now eighty year old sculptor and conceptual artist is one of the greatest to have ever done it.

Why? Because he finds tragic and uplifting stories, allegories, and metaphors in ordinary objects. Things like a chipped mirror, a cigarette butt, or a fur coat that we see all the time, but never take the time to look at.

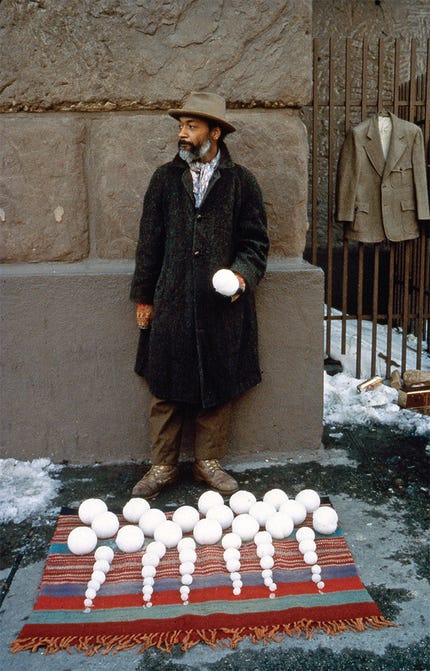

When Hammons walked the streets of Los Angeles and New York searching for the objects he used in his most famous sculptures, he was actually searching for their shadows– the stories in and around those objects. The block party that scattered chicken bones on the sidewalk. The vicious cycles haunting gin bottles piled in a park. The institutional neglect of a bent and net-less basketball hoop and the love of the game that tied twine to the rim as a replacement. Hammons approaches these stories obliquely– rummaged through their litter and debris. Stalking their comings and goings. Then Hammons takes those objects and transfigured them into altars and sites of reflection on the people they touched, their stories, and the human condition as a whole.

That is the first lesson Hammons can teach entrepreneurs: To find multitudes in a single data point. To seek the rich stories, values, and patterns behind seemingly isolated acts. As Eric Reis reminds entrepreneurs, “metrics are people, too... breathing, thinking, buying individuals” (88). A favorite quote of Hammons’ from jazz master Ornette Coleman is “follow the idea of the song, not the song itself… not the sound” (Art Forum). This is the opposite of spinning a story. Hammons rarely bites off more than he can chew or makes a whole lot out of nothing. Rather, he sees a whole lot in what may look like nothing at first glance. In art, as in business, you need to “go and see for yourself firsthand” rather than making assumptions or relying on what others say about the problem (Jeffrey Liker, 223).

What this means in practice is that entrepreneurs must be able to discover the value proposition (and externalities) of their product to all parties involved, and how their product can become integral to their customer’s behavior patterns and stories. The Founder of Misfits Market, Abhi Ramesh, did just this when he recognized that consumers were open to, and even interested in, imperfect produce that traditional retail channels assumed were undesirable. Ramesh saw a story of undervalued “misfit” Number 2 and 3 apples piled in orchards across the U.S. and built a unicorn company (CNBC). A purely marketing example comes from Chinese liquor brand Xi Jiu’s engagement-first campaign in 2017 accomplished this by tying their products to customers’ identities and food cultures. Xi Jiu partnered with Tencent on a viral series of hour-long shows in which known Chinese chefs prepared regional dishes and paired them with Xi Jiu products (Kimberly Whitler, HBR).

Hammons’ approach is distilled in his Six Projects in Alexandria (2008). Rather than present artworks in a gallery, he handed visitors cards that mapped six “artworks” on the streets of Alexandria for them to go see. These included a tree with a leaning trunk someone had painted turquoise, and a frail wooden chair someone had secured to a post with a heavy chain. For Hammons, pointing out these objects as worthy of contemplation was enough to direct people’s attention to the stories they told. Like a data scientist who identified such compelling patterns he could just point to them, and his audience could immediately grasp their meaning.

This is the second lesson Hammons can teach us: cast a wide net and avoid staking yourself too firmly on any one perspective. This begs questions that are broad in scope despite emerging from local problems, and it engenders products that are relevant at scale. Entrepreneurs must consider what their product(s) mean in unique market segments, without losing sight of local needs. Every business needs to start somewhere, and their beachhead market is usually the one with the most acute or immediate problem. Bruce Moeller, CEO of DriveCam (2004-8), cites empathizing with customer feedback as key to overturning the company’s faulty assumptions. He discovered that DriveCam cameras should record inward, and that cab drivers could be a beachhead market– insights that paved the way to reaching $50M in annual revenue (Cooper & Vlaskovits, 49).

Everyone has an opinion– entrepreneurs are no exception– but these should spur us to new learnings, rather than distort new information we encounter. Hammons’ local references are always threaded beyond any single experience or geography. His early monoprints of disenfranchised Black figures were first presented in Black art centers, but speak to a wider urge for freedom and control. His later bound and concealed Baroque mirrors and grand canvases were first presented on the Upper East Side, but speak to a wider urge to recede from prying eyes and defend our self image.

All this and more has made Hammons’ work highly sought after, despite little effort on his part to be recognized by institutions or at auction. One of the best places to see his work today is at the Pinault Collection in Paris, where the Kering luxury mogul has an entire gallery dedicated to his collection of works by Hammons.